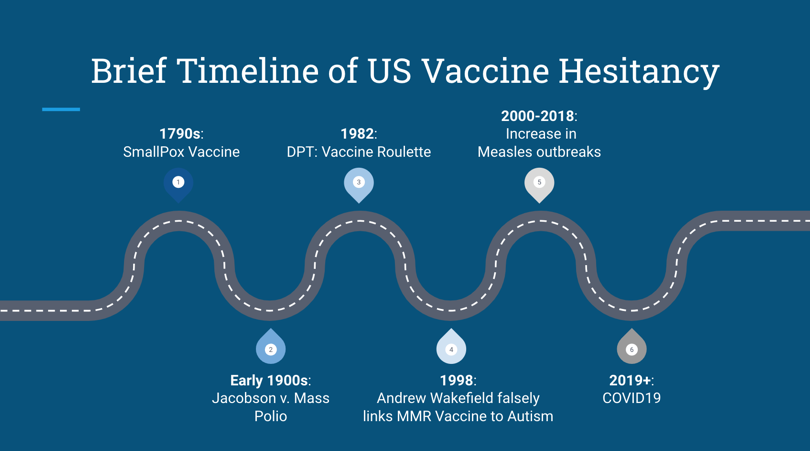

Over the last two decades, anti-vaccine activism has grown from a fringe subculture into a well organized, networked movement. This evolution is leading to severe public health repercussions. with the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbating this issue and magnifying the spread of vaccine misinformation. An article from the National Library of Medicine describes three noteworthy patterns in this movement.

1. Progression into right-wing identity and activism

2. Networked activism

3. Harassing and threatening health-care and public health professionals

One of the major public health outcomes seen as a rise of this movement is the decline in childhood vaccination rates, which in turn is leading to increased occurrence in vaccine preventable diseases. The Journal of Pediatric Pharmacology and Therapeutics describes four overarching categories to describe the reasons that parents refuse, delay, or are hesitant to vaccinate their children.

1. Religious reasons

2. Personal beliefs/Philosophical concerns

3. Safety concerns

4. A desire for more information from healthcare providers

These concerns lead to a wide spectrum of decisions, ranging from parents delaying vaccinations so that they are more spread out, to parents completely refusing all vaccinations. Vaccinations play a vita role in preventing diseases in children. There are no federal laws regarding vaccine administration, but each state has laws dictating which vaccinations are required for children before attending school. All 50 states allow medical exceptions, such as for those who are immune compromised or those allergic to various vaccine components. There are 30 states that allow exemptions for those whose parents cite religious reasons. There are 18 states that make special accommodations for those expressing philisopical reasons. however, states with more lenient laws are shown to have increased rates of exemptions granted, leading to greater vulnerability in the population. In fact, the outcomes of these exemptions are arising. 30 states reported to the CDC that the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a decreased rate of vaccination coverage for the 2021-22 school year. This was due to reduced access, but also due to "local or school level extensions of grade period of provisional enrollment policies." In 2021, one in five children under the age of one year did not have any vaccine doses.

There has also been shown to be large disparities in childhood vaccination rates by race, incomes nd geography. According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, from the years 2018 to 2022, children born in the United States from 2017 to 2018 who were uninsured, Black, Hispanic, and/or had family income below the federal poverty level had lower childhood vaccination coverage than those who were privately insured, white, and/or had family incomes at or above the federal poverty lines. These children were also more likely to miss routine immunizations. This was shown to be due to transportation challenges, lack of access to routine pediatric care, and greater parental vaccine hesitancy.

|

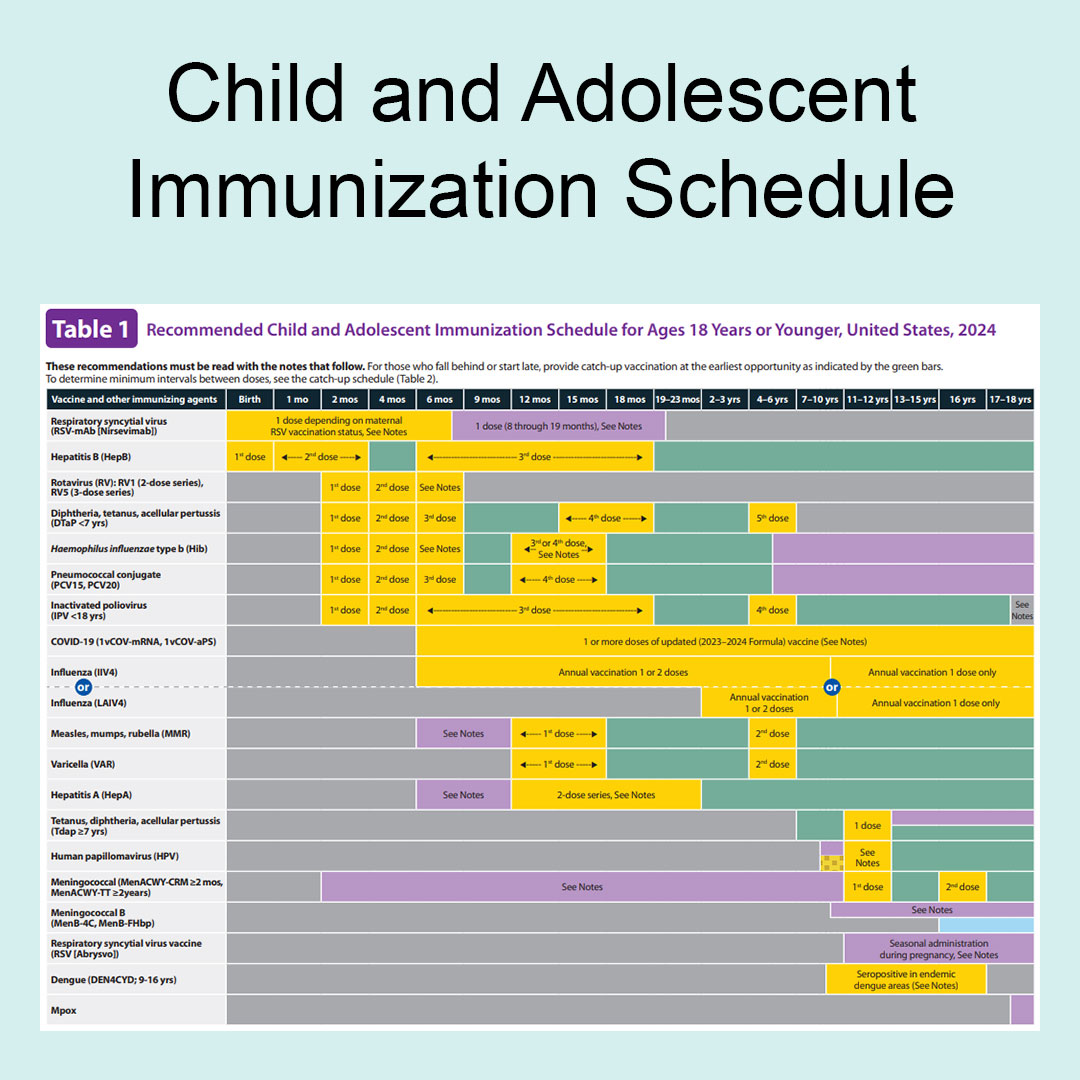

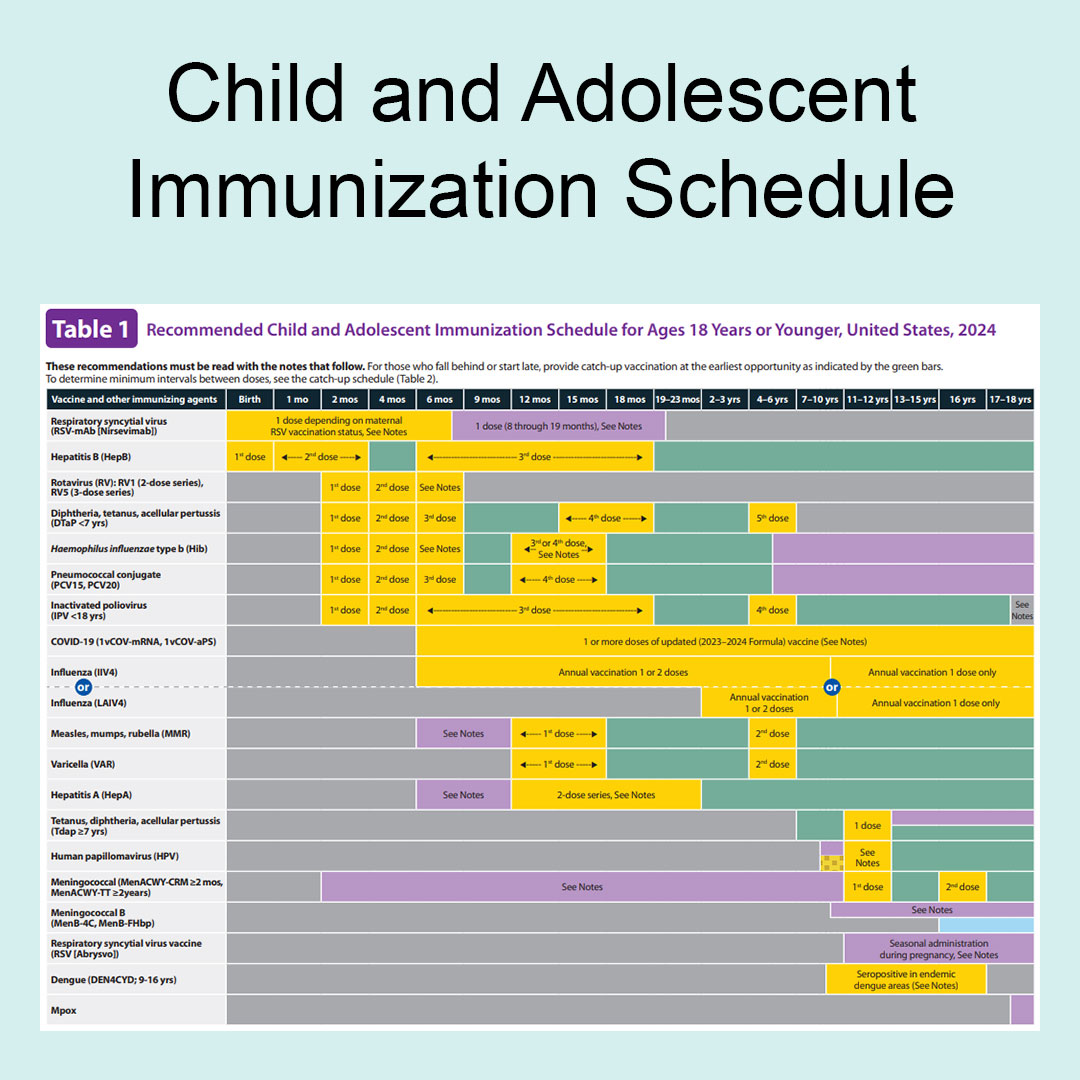

CDC: Recommendations for Ages 18 and Younger, United States, 2024

|

Routine childhood immunization has been shown to continuously yield considerable sustained reductions in the incidence across targeted diseases, such as influenza, measles, mumps, polio, rubella, etc. These diseases can have serious outcomes when contracted. Measles can cause brain swelling, leading to permanent brain damage or even death. Mumps can cause permanent deafness. Meningitis can also lead to permanent deafness or brain damage. Polio can cause permanent paralysis. The United States saw its first case of Polio since 1979 in July of 2022, where a man who was unvaccinated was paralyzed as a result f the infection. As of March 18, 2024, Measles cases in the Untited States have already reached last year's total of 58, with most of these cases being unvaccinated children. On average, one out of five unvaccinated people diagnosed with Measles end up needing to be hospitalized. A recent outbreak in Ohio even saw over 40% of infants and children infected with Measles in the hospital. The CDC describes Measles, stating that it "is so contagious that if one person has it, 9 out of 10 people of all ages around him or her will also become protected if they are not protected." Thus, delaying or refusing a child's vaccine proposes risk to their own health and safety, but also that of others. Those most at risk include people with weakened immune systems due to other medications or diseases, people with chronic medical conditions, newborn babies who are too young to be vaccinated against most diseases, and the elderly.

The decline in childhood vaccination rates can be addressed by improving access to and boosting confidence in childhood vaccinations. Some suggested interventions include:

- Bolstering resources for immunization programs through the federal Vaccines for Children (VFC) and Section 317 programs

- Expanding the vaccination workforce through policies that facilitate provider enrollment in the VFC program and support vaccinators, such as school nurses and pharmacists

- Increasing vaccine reimbursement to cover costs associated with vaccination, such as vaccine education and reducing administrative burdens

- Tightening and reenforcing school vaccine requirements that have been effective in producing high vaccination rates

- Engaging trusted community leaders, such as health care providers, school staff, and faith-based organizations, to counter vaccine disinformation with accurate and effective messaging